Introduction

Japan's economic performance after WW II till 1990 was exceptional. Japan managed to rise from a country decimated by a world war to one of the wealthiest nations on earth in only four decades.

Especially the high-growth era between 1950 and 1973 flabbergasted many Japan observers. Neither the two oil shocks of the 1970's nor the orchestrated Yen revaluation of the mid 1980's, where the Yen appreciated significantly, put any breaks on the relentless rise of Japan. Quite contrarily, it appeared to had made Japan even more powerful. At the latest when corporate Japan began trophy shopping in the U.S, and started to hoard U.S. icons like the Rockefeller Centre and Universal studios, the sentiment towards corporate Japan started to shift, especially in the U.S. Had it been envied before was it now feared.

Many observers were convinced that the unique governance system of Japan, the J- System, with its three pillars of main banks, Keiretsu and lifetime employment, was the main reason behind corporate Japan's success and seemingly unstoppable ascent.

During that time many pundits marketed the J- System as the endpoint of an efficient corporate governance system. Far superior to the Anglo-Saxon model of shareholder primacy and market disciplin. Even the Economist, usually not known for a socialist agenda, suggested that Japan's intercorporate shareholding structure appeared to have done a better job than most Western economies of filling the "vacuum at the heart of capitalism" that resulted from the fragmentation of ownership accompanying the rise of the modern corporation. Many others also claimed that the traditional public corporations, with large numbers of dispersed shareholders, had outlived its usefulness. They advised the West that it should take the J- System as its model. They advocated the replacement of open stock markets with large-block investments by financial institutions that serve as both equity and debt holders in highly leveraged firms. (Gerlach)

How time has changed! Since the bubble has popped the J- System has come at the center of criticism by foreign observers. Especially by the advocates of the Anglo-Saxon model of corporate governance, which is now marketed vigorously as the endpoint of an efficient corporate governance system. The J- System, on the other hand, has been regarded as a significant structural barrier for newcomers in the Japanese market and a hindrance to the powers of "animal spirit" and Schumpeter’s' "constructive destruction". Broadly speaking the J- System now is held responsible for Japan's inefficient capital markets, inefficient corporate governance and suboptimal economic performance. This perception has significantly heightened by the unsuccessful attempts of overseas investors, such as Steel Partners and T. Boone Pickens, to gain a significant voice in the internal affairs of corporate Japan through the same mechanisms of stock acquisition and takeovers that they have used in the United States.

A lot has been written lately about how outdated the J- System has become. But little is known what really constitutes the J- System of corporate governance and control in Japan. This serious of posts intends to change that and shed some light on the J- System.

In the first part the main bank system was presented.

This second part will be dedicated to presenting and scrutinizing the Japanese Keiretsu network system.

Personal Remarks

I am well aware that this serious of posts does raise important questions regarding the optimal organization of exchange in an economy, i.e. is stakeholder primacy (J- System) or shareholder primacy (Anglo- Saxon System) the most appropriate framework of corporate governance to ensure overall economic efficiency. But those topics will not be dealt with as it would go beyond the scope of this serious of posts.

Zaibatsu

The Zaibatsu system was the predecessor of the Keiretsu system. Many of their origins date back to the Tokugawa regime (1603-1868). For example Misui was a political merchant that, among other things, provided financial services to the Tokugawa regime. Others, like Mitsubishi and Yasuda, where founded during and after the Mejii Restauration (1877-1890). At the beginning the "Mejii" Zaibatsu were less diversified than the "Tokugawa" Zaibatsu. But with increasing government protection, subsidies, loans, privatization, etc. they subsequently had grown and diversified in patterns broadly similar to the older Zaibatsu. (Grabowiecki)

Japan had been late and thus on its own path of industrialization and technological innovation. It had been forced to learn new production methods from the west rapidly and to invest in new processes with which it was unfamiliar. Japanese industrial organization had been characterized by rapid rates of change in market conditions and technological capabilities, as well as a permanent evolution in government policies and industrial structure.

The Zaibatsu arrangements emerged within this context. It represented a compromise between the simultaneous needs to retain control over scarce resources and to exploit expanding economic opportunities. Not only did Zaibatsu expand through the kind of elaborate internal hierarchies that dominated business development and where adapted from the United States, but also through subdivisions into quasi-independent units. The Zaibatsu diversified far more completely than their corporate counterparts in the United States. (Gerlach)

Concerning the organizational structure and governance of the Zaibatsu system, guaranteeing family control over the entire Zaibatsu network of (in its day-to-day operations) increasingly decentralized subsidiaries has to be seen as its essential feature. A holding company (Honsha) was at the very top of this network of suppliers, subsidiaries and dependent firms, wielding control over those firms. Issuing stocks by the Zaibatsu subsidiaries allowed to expand into new business ventures and created an increasing pyramidal Zaibatsu structure of member firms over time. It allowed to raise a tremendous amount of private capital, while the founding family retained complete control over the holding company and its subsidiaries (network firms) (Grabowiecki)

An additional important source of control by the honsha over its subsidiaries in the prewar Zaibatsu was through directors sent out to the subsidiary firms. For example, by 1945 the Mitsui holding company held twenty-one directorships in its subsidiaries, Sumitomo fifty-one, and Mitsubishi eighty-five, or an average of about two to four directors per first-line subsidiary (Gerlach).

The process of forming new subsidiaries and subsequent share offerings of the network firms to the public was repeated till the family ran out of promising investment opportunities. (Grabowiecki)

|

| (Zaibatsu) |

-1-

From Zaibatsu to Keiretsu

Zaibatsu holding companies were dissolved and monopolistic companies were divided by the Allied forces at the end of World War II. (Ito) But the dissolution of the Zaibatsu was a far cry from the kind of universal overhaul of the Japanese economic system that the protagonists had intended.

Surely, the dissolution successfully eliminated the position of the Zaibatsu families, dissolved the Zaibatsu honsha, dismissed former executives, and broke up the trading firms and large manufacturing operations. But this was only a fraction of the networks of connections that held together the various elements constituting the group. The most important connections to the past remained intact.

Especially the new executives, which predominantly came from middle management in the old subsidiaries, maintained and developed ongoing personal connections with managers in other subsidiaries extending back to the war and prewar years. Moreover, many were delegated to their new positions by the former top executives of the Zaibatsu. In addition, although the leading manufacturing and trading houses of the Zaibatsu group were broken up, but regrouped later, the group banks were not. These banks had already taken up a position during the wartime period as leading financiers to the group. After the war these banks took on the role of filling the power vacuum left by the dissolution of the Zaibatsu holding company. Their position was enhanced considerably by the scarcity of capital during the postwar period.

Another form of continuity was the maintenance of significant cross shareholdings between subsidiaries and main bank. Unlike the holding company structure and family holdings, these shareholdings were not dismantled after the Second World War. Those cross shareholdings served as another remaining fundament and structure on and around which the companies began regrouping itself. It does not come by surprise that when, for example, Sumitomo began meeting again in the early 1950s, all eleven of its old first-line subsidiaries, now each independent operations, took part in the first meeting to form the predecessor of the old Zaibatsu System, the Keiretsu System. (Gerlach)

Keiretsu

After WWII, like after the Mejii restauration, Japan found itself in a very unique economic position. Again it was on its own path of rebuilding, re-industrialization and re-technologization. Post World War government and corporate policies in Japan geared towards technology catch-up and fast export-led economic growth. Those policies formed again the backdrop to a particular industrial architecture in Japan: The so called Keiretsu (=inter- market business groups). (Schaede)

The Keiretsu system of corporate organization is quite unique and pretty opaque for many westerners, as it is neither that of Alfred Chandler's "visible hand" nor that of Adam Smith's "invisible hand". It is neither the solid structures of formal administration nor the autonomously self-regulating processes of impersonal markets. It is a system of hands interlocked in complex networks of formal and informal inter- firm relationships. (Gerlach)

As outlined in the previous paragraph present-day Keiretsu groups have their origins in the pre-war Zaibatsu structure. They are largely composed of enterprises that were spun off from the Zaibatsu. Most of them quickly became very successful in the old markets they had been engaged before and during WWII and new markets they were developing during the post war period. They kept on the diversification strategy followed under the Zaibatsu system, either by developing their own new enterprises or by bringing in companies from outside, forming overall alliances (e.g., the Matsushita or Hitachi groups). (Gerlach)

The Keiretsu system mainly consists of formally and informally specified relations among large firms (composed almost entirely of Japan’s “blue chip” companies) as main pillars, small firms as supporting staff and main banks and trading houses as central operators of corporate finance and organizer of overall business procedures. (Schaede)

The tie-ups in Japan come in two main forms:

- Horizontal Keiretsu (Kinyu Keiretsu): Large, inter-market groups

- Vertical Keiretsu (Shihon Keiretsu): a) Production Keiretsu; Between a manufacturer (end producer) and its suppliers, distributors, dealers and retailers; b) Distribution Keiertsu: Linear systems of distributors that operate under the name of a large-scale manufacturer, or sometimes a wholesaler.

Although this division into this two types of Keiretsu is cited in numerous literature concerning the subject, one has to keep in mind that it does not reflect fully the true character of relations occurring in those types of Keiretsu structures. Kinyu Keiretsu can be translated into financial Keiretsu. But financial relations are not the only connector of its group members. Although the position of the main bank, and thus the importance of credit relations, is pivotal in this Keiretsu system, production as well as trade relations are of great importance too. (Grabowiecki)

Shihon Keiretsu, on the other hand, can be translated into capital Keiretsu. It suggests a dominant role of capital relations. Capital relations, in form of share ownership, do play an important role in the vertical Keiretsu, but it is the production and distribution relations between the main subject of the group (the apex company) and the network of subsidiaries that are crucial. They are the distinctive feature of the vertical Keiretsu to the horizontal one. Capital relations play a role analogous to the one they play in a horizontal keiretsu. Thus, they are not a distinguishing feature differentiating this type of Keiretsu from the alternative one. They are rather a characteristic feature of both types of Keiretsu.(Grabowiecki)

Abovementioned makes apparent that a clear cut presentation of the Keiretsu system is complicated. A variety of alliances exist and it is often difficult defining membership. Furthermore, often there are misconceptions concerning the nature and purposes of different Keiretsu systems. The assumption is often made that Keiretsu and other alliance forms are uniquely endowed institutions with clearly defined boundaries, when the reality more often is of blurred boundaries and overlapping affiliations. (Gerlach)

Especially after WW II and during Japan's high growth era the Keiretsu was the critical vehicle through which the Japanese capital was channeled into enterprises and investment projects that were considered promising and essential. Keiretsu were believed to be the engines of innovation and new business formation. (Grabowieckie) While the Keiretsu expanded through forming and including new members in promising growth areas the scale and complexity in its group structure increased significantly. This evolution of alliances has not been a wholesale replacement of old forms of organization with new firms, but rather a laying of newer and often higher-level structures on top of preexisting ones.This new combination usually coexists with other groups serving other organizational purposes. (Gerlach)

In addition, Keiretsu play a critical role when it comes to restructuring of declining industries. Many see the real strength of the J-system in the speedy reaction to external shocks (e.g. oil crisis/ revaluation of the yen after the plaza accord) and a swift and smooth transition from stagnant or declining industries to sectors with higher growth potential and competitive advantage. In contrast to the west, those structural adjustments are mostly carried out without social unrest, mass layoffs, and direct government subsidy and business failures. (Grabowiecki)

Especially after the Japan bubble popped and Japan entered into the so called "two lost decades" many market pundits have been evoking the end of the Keiretsu and J- System. Granted a lot has changed in corporate Japan. But still most Keiretsu in Japan are well and alive.

One rationality for maintaining a network and alliance structure in Japan up to now is that although the contemporary Japanese economy is concurrently located at the industrial frontier across a wide variety of sectors, the basic reality of technological and organizational uncertainty has not really changed. New forms of uncertainty and changes born of being a technological leader continue. Thus, the underlying reality that no single firm has the resources to carry out all of its objectives remains intact. The Keiretsu, like the Zaibatsu before them, have proved flexible in accommodating those constantly changing technological and market conditions. (Gerlach)

-2-

Horizontal Keiretsu

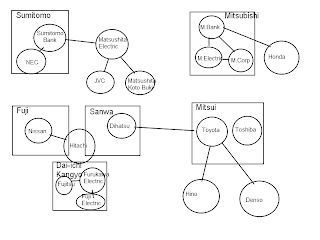

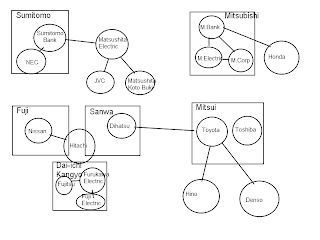

The so called „six horizontal Keiretsu" form the core of this industrial architecture in Japan. The "six horizontal keiretsu" can be subdivided in two forms (Shaede)

- Three that are descendants of the prewar Zaibatsu system (Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo)

- And three that were formed on the initiative of a bank and anchored around it (Fuyō, Sanwa, and Dai-Ichi Kangyō (DIK)).

The core of a horizontal Keiretsu includes a large city bank, a general trading companies (Sogo Shosha) and often also a life insurance company (Kanji Gaisha). It is surrounded by other financial institutions and large industrial companies. (Grabowiecki) Although cross shareholding among group members are a common feature of the horizontal Keiretsu, no company is dominant in terms of ownership stake. (Shaede)

Each horizontal Keiretsu is composed of between twenty and forty large companies in different industries. Especially strongly represented are the key industries of the postwar high growth era (heavy industries, petrochemicals, materials processing, as well as banking and trading). Mainly the large industrial companies forming part of the horizontal Keiretsu have an extensive network of subsidiaries. The most prominent horizontal Keiretsu are Mitsui, Mitsubishi and Sumitomo. (Grabowiecki)

The objective when forming the Keiretsu was to extend and diversify a group's sectorial span. (Ito). The groups follow a fairly strict rule referred to as “one-setism”. "One-setism" describes the tendency among the major groupings to have only one company representing each significant industry. (Gerlach) (Shaed) The one-set pattern is followed most strictly among the former Zaibatsu groups. Sanwa and Dai-Ichi Kangyo bank groups do not follow the "one-setism" pattern as strictly, as there are internal duplications in several trading and commerce, chemicals, steel, and electrical machine companies. (Gerlach)

Personnel movements within the horizontal Keiretsu are limited to the level of the board of directors. Also the flow of goods are limited. Horizontal Keiretsu firms rely approximately on 13% of purchases and 15% of sales internally. (Grabowiecki)

The Keiretsu Presidents' Councel

The Mitsubishi group is a case in point for a horizontal Keiretsu. As of October 1993 twenty-nine firms were members of the Keiretsu. Among others, it included financial institutions (Mitsubishi Bank, Mitsubishi Trust, Meiji Life, Tokyo Marine and Fire), a trading companie (Mitsubishi Corporation), shipbuilding and other heavy manufacturing companies (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries), as well as an automobile manufacturer (Mitsubishi Motors). The group's core is most often defined by membership in the Mitsubishi "president's club". (Ito)

The members of a Keiretsu are linked through a variety of intercorporate executive councils. They serve as a forum for managers from different levels of the companies involved in a Keiretsu. The most prominent is the abovementioned group presidents' council (president’s club/ shacho- kai). It brings together the chief executive officers from the group's core companies and is a kind of informal community council. The membership is strictly limited to a set of core members.

The broader form (for vertical Keiretsu) is the kyoryoku-kai format, bringing together the parent firm (Toyota, Hitachi, etc.) and its first-tier subsidiaries. Rather than being a command centre, the shacho -kai and kyoryoku- kai should be rather seen as a forum for discussions on matters of mutual concern, i.e. to establish an identity for the group and its participants, instilling a sense of coherence, creation of a setting in which issues of group-wide concern may be negotiated and, less often, arranging for assistance for companies in trouble, resolving conflicts among members, or disciplining deviant group companies.

But most often nothing particular is being discussed and the meeting is merely an opportunity to exchange views with other chief executives and to socialize. The atmosphere is said to be one of camaraderie rather than of a formal meeting with a defined agenda. In addition to the presidence club, more informal ("old-boy" get-together/ ob-kai) councils do often exist too. They are primarily orientated toward playing golf, as well as a variety of regular meetings for directors, vice presidents, and division managers for the purposes of discussing corporate planning, public relations, and other group-wide activities. (Gerlach)

Each of the horizontal Keiretsu maintains a somewhat different reputation within the Japanese business community. Mitsui is rather recognized for its "individualism", as it is relatively loosely organized and individual companies and personalities involved in the network are rather strong. Mitsubishi, on the other hand, is often referred as the "organization" because of its tight, quasi-hierarchical, structure and the large number of group projects that bring together its member firms.

Finally, "cohesion" is often used when describing the Sumitomo Keiretsu, since it has maintained only a small core set of firms and it has been the Keiretsu most reluctant to expand its core membership beyond its original Zaibatsu lineage. Many observers see the relationships and organization within the Keiretsu as part of a wider social competition. They bring forth the argument that, for example, the „battle" between Sumitomo and Mitsubishi is really one between two different business cultures. The rationalistic and commercial orientation of Osaka (Sumitomos' home) and the social and political orientation of Tokyo (Mitsubishi's home). (Gerlach)

.png) |

| (Horizontal Keiretsu) |

-3-

Vertical Keiretsu

Vertical Keiretsu are networks of subsidiaries operating within large corporations and subordinated to them by means of capital and long-term production/ distribution relationships. (Grabowiecki) Those subsidiaries perform many of the functions typically carried out in-house by U.S. firms through their own divisions.

Within the vertical Keiretsu, exchange between the parent and satellite firms is embedded in a dense network of ongoing relationships, as various forms of information, technical and financial assistance, and managerial expertise are provided on a reciprocal basis. (Gerlach) Examples for vertical Keiretsu are Toyota, Toshiba and Hitachi. But basically every large Japanese manufacture heads a vertical Keiretsu to a certain extent. (Grabowiecki)

.png) |

| (Vertical Keiretsu at the beginning) |

The vertical Keiretsu is a fundamentally different type of network from the horizontal Keiretsu previously described. Vertical Keiretsu mainly differ in scope, number and structure. In a horizontal Keiretsu predominates a rather loose relation of different size and different branch enterprises.

Whereas, the vertical Keiretsu is often much more tightly coordinated. They usually have a kind of a pyramidal structure of shareholding and personal transfer (from core company to fist-tier suppliers to second-tier supplier, etc.) in combination with a much more centralized executive management. The core company holds controlling shares in the first tier, key subsidiaries. The first- tier company holds controlling shares in the second-tier company, and so on.

In addition, the vertical Keiretsu is characterized by a high degree of branch specialization. (Grabowiecki). When compared to a horizontal Keiretsu it is worth noting that it is the vertical Keiretsu that is more likely to exhibit anticompetitive behavior and the Keiretsu that resembles the pre-war Zaibatsu system. (Ito)

Vertical Keiretsu, for most companies, are composed of two types of subsidiaries (network firms):

- An independent firm that developed a long-standing relationship with the core company (usually a supplier or distributor)

- Firms that were created by a divisional spin-off by the core company (Kogaisha).

(Grabowiecki)

The second type of subsidiary companies being part of a vertical Keiretsu networks take on patterns of capital investment and trade similar to their parent companies'. They are recreating alliance structures in an expanded form, resulting in the gradual increase of overall membership. Toyota Motor Corp., for example, defines the Toyota Group as fourteen key companies, most of which were spun off of the parent company at some point in the past (e.g., Nippondenso and Toyota Autobody).(Gerlach)

.png) |

| Vertical Keiretsu after evolving over time |

Companies can differ in the extent to which the core company owns a controlling share in the group firms. Some like Hitachi, Sony, and Suzuki hold up to 80% of the shares of group companies. Others, like Toshiba and Toyota, fewer than 20%. (Grabowiecki)

Although the core company itself has a range of business divisions, for example Matsushita Electric has over forty business divisions producing a wide range of products, from office equipment to home appliance, it will always concentrate its activities on high- value- added manufacturing. The group companies (subsidiaries), on the other hand, typically engage in one of three types of activities:

- Manufacturing and sub assembling of components

Within the large vertical Keiretsu, representative directors are usually dispatched from the parent manufacturer to its subsidiaries in order to wield control over and monitor them. Toyota Motors, for example, sends an average of three to six representative directors to each of its first-tier subsidiaries, as do Nissan, Hitachi, Matsushita, and other large parent industrial companies. (Gerlach) Contrary to the quasi related business, which have considerable independence, sale and distribution companies are completely dependent on the core company, as they are dedicated to handling solely the group's products. They concentrate on getting the final products, produced by the core company, to the customer. Manufacturing subsidiaries are located somewhere in the middle concerning its independency to the core company. (Grabowiecki)

Regarding the beneficial features of the vertical Keiretsu it is often stated that trust, reputation for quality, and long-term commitment are all crucial elements of the repeated transactions between a manufacturer and its suppliers and distributors. Frequently checking the quality of each individual part and product when it is delivered or sold is difficult and time consuming. Furthermore, since "lean production" (= "just-in-time delivery" / cutting back on inventory) has become a hallmark of Japanese manufacturing, it is extremely important that suppliers make every effort to fill a manufacturer's orders on time, as well as in expected quantity and quality. The manufacturer, on the other hand, evaluates its suppliers' records of the delivery and rewards them with an implicit guarantee of continuing orders. (Ito)

Once again, although horizontal and vertical Keiretsu were portrayed so far as being quite distinct, they are highly intertwined. The parent firm, and by extension its satellites, are embedded in a broader set of relationships defined by a horizontal Keiretsu. (Gerlach)

For example is the Toyota vertical Keiretsu linked mainly to the Mitsui horizontal Keiretsu. Nissan is within Fuji, NEC in Sumitomo, and so forth. By the same token, where vertical Keiretsu span horizontal Keiretsu, they thereby tether them together. Toyota is a Mitsui-kai member, and most Toyota group companies thus deal with Toyota's primary bank. (Grabowiecki) Often the phenomenon is referred to as "the second-order environment" of the Japanese Keiretsu system. It comprises more loosely coupled relationships among dozens of firms in diverse industries. Internal exchange is generally less pervasive than at the firm or vertical Keiretsu level, but the identity of the group nevertheless imparts structural and symbolic significance to these exchanges. (Gerlach)

|

| (How Keiretsu interconnect) |

-4-

The Rationality Behind the Keiretsu System

The rationality behind forming a Keiretsu system can be explained in two aspects: The ownership motive and the functional motive.

The ownership motive

The ownership motive is quite strait forward. Keiretsu are aimed to shield corporate Japan from the "threats" of free market competition in the form of corporate control and takeovers. This is accomplished by engaging in cross-shareholdings with other group members. A single firm’s ownership stake in each of the other companies is usually rather small (15% to 30% of total group equity outstanding). (Shaed) But this rather seemingly small number ignores several important facts.

Firstly, many of the "friendly" shareholders to the management are not included in these figures, i.e. they are not formally identifiable as forming part of a Keiretsu network. But they are nevertheless linked structurally through reciprocal and strategic shareholding positions with the company. Most large Japanese firms have in reality well over half of their total equity controlled by stable shareholders. In the case of some firms, such as commercial banks and other financial institutions, this figure gets over 90 percent. (Gerlach)

Secondly, both affiliated and unaffiliated intercorporate investors are disproportionately represented among a firms' leading shareholders. The top-ten shareholders often control over 25 percent of outstanding shares in all major intermarket Keiretsu and over 50 percent in the older, Zaibatsu-based groups. (Gerlach)

Furthermore, the influence of those intercorporate investors extends substantially beyond what the raw percentages of shareholdings would indicate, as these strategic shareholders are the ones that are best able to create voting coalitions if engagement in management policy is needed. (Gerlach)

Finally, the main bank has a crucial role too concerning the ownership motive. Although the main bank does not overtly intervene with the management of firms in normal times, the control right is expected to shift to the main bank in a critical corporate-value state. (Aoki) The main banks’ substantial debt and equity positions with the client companies give them the leverage to use their information to influence managerial decisions and, when necessary, replace senior management and placing more members of the bank on company boards. The main bank is even in the position to liquidate a company (=contingent governance). But one has to keep in mind that the main bank will be extremely cautious about closing down a failing business by calling in loans. Often, it will first send in an extra management team, even including a replacement for the president of the firm if necessary. (Pushniak) (Aoki)

Summing up the abovementioned, in the Keiretsu system white-collar and blue-collar employees and the main bank are the quasi-owners of the firm and not the shareholders. (Pushniak) The network of company interrelationships has been preventing corporate Japan from corporate raider and hostile take-over bids. Unfriendly M&A activities, according to the advocates of an Anglo-Saxon system of corporate governance the prerequisite of an open and efficient capital market, are almost not possible in the J- System. But not few argue that the absence of unfriendly M&A activities does not imply that the market of corporate control in Japan is ineffective. Those duties are just performed internally within the Keiretsu system. The efficiency enhancing pressure to perform is not generated by market pressure but by endogenization, informalization and diffusion, which is the Japanese method. (Grabowiecki)

The functional motive

The functional motive of forming a Keiretsu is more complex. In the following paragraph some significant functions of the Keiretsu system will be presented.

One rationality for forming and taking part in a Keiretsu is the distribution of risk within the Keiretsu. Some argue that minimizing risk was the primary objective of bringing into existence a Keiretsu. By joining a Keiretsu, companies basically get an insurance, not only against corporate control issues (see operational rationality), but also stock market fluctuations, precipitous drops in sales, financial uncertainty, etc. (Shaed) The group members share risk and reduce risk for individual members.

The manifold and overabundant mutual business relations within the Keiretsu act as a "natural hedge". Only external risks have to be secured not intra-company risks. Furthermore, when the individual members are perceived as a unit, and considering the extent of sales diversification, than a Keiretsu basically creates a diversified portfolio. (Grabowiecki) The umbrella of the company group, in combination with interconnection within the Keiretsu system, protect its group members from excessive risk. Especially for operationally and financially high levered small companies, which are operating in an environment of rapid technological “catch-up”, risk minimization was and is their single most important rationality forming part of a Keiretsu, as their biggest concern is survival. (Shaed)

Another rationality for forming a Keiretsu is the organization of overall business procedures of the Keiretsu group. A pivotal role here is assigned to the Trading houses (see the following paragraph) and the numerous service groups within the Keiretsu group. The service groups perform special associated functions, which are available to the Keiretsu group members, such as commerce, insurance, shipping, warehousing, etc. Each link in the production chain can be supplied with optimal level of input and input prices. It can be achieved more efficiently than by a fully integrated company, because the system openness within the Keiretsu produces significant flexibility. (Grabowiecki)

Last but not least, the Keiretsu fulfills important functions concerning corporate finance within the system. The two fundamental tasks are:

- Differing credit and investment requirements are coordinated internally ==> reduced risk and frees up more financial resources for the main bank; especially in times of crisis this provides a powerful risk management tool

- Providing access to international financial markets which would be unavailable to smaller and less known group members. The bank bundles individual capital requirements and tries to satisfy them efficiently.

Especially the second point is key for the success of a Keiretsu. If successfully implemented it reduces interest charges, especially for the smaller group members. Many conceive the procurement of cheap funding as an extraordinarily strength of Keiretsu system, as it allows aggressive expansion with relatively cheap funds. Basically it is perceived as a provision of risk capital at minimal cost and at any given point in time (even in times of general uncertainty). (Grabowiecki)

Companies operating within a Keiretsu are said to have low profit margins. That is true, because the structure of a Keiretsu demands that intra-group transactions are settled on transfer prices rather than market prices. The objective is to even out the aggregate profit of the group as a whole. Contra payments are granted to those members that fail to make a profit. From the Keiretsu point of view this basically is a rational strategy in order to maximize the success of the company groups as a whole. (Grabowiecki)

But it leads to irritation, especially in the west. Intra-group transactions often have been a source of irritation and problems especially in joint ventures between Japanese Keiretsu members and foreign partners. Usually the Japanese managers in the venture want to procure upstream products and services through the Keiretsu members wherever possible. The western partners, on the other hand, want to buy on the open market. A resolution is often effected through the intervention and personal influence of the Japanese head of the joint venture. Often they are able to influence group members to come down to competitive rates. The purchases would still come through the same affiliated firms, only they would reflect something closer the prevailing market price. (Gerlach)

-5-

The Role of the Trading Houses within the Keiretsu System

As mentioned above the organization of overall business procedures of the Keiretsu group is another rationality for forming a Keiretsu. It encompasses all sectors (good procurement, marketing, logistics, warehousing, etc.). The trading houses (=Sogo Shosha) are key in fulfilling that function. They are the main actor in the organization of product market relationships of both kind. The Sogo Shosha are to the Keiretsu trading network what banks are to its capital networks. Trading Houses are the most centrally positioned firms, with direct linkages to most other companies in the group. For the majority of intermediate product manufacturers in a Keiretsu, they are the leading overall supplier and customer.

Moreover, they are important as an organizer of small- and large-scale group projects. (Gerlach) The trading houses coordinate and generate supply and demand on the home market within the Keiretsu groups. They balance out all possible intra-Keiretsu transitions on the external good and service market. This coordination is said to generate economies of scale and lead to significant cost reduction. Furthermore, it is argued that, combined with lower fluctuation levels, it generates positive externalities in form of increased efficiency and minimized cost for risk management. (Grabowieckie)

In addition, trading houses traditionally have been working in Japan as information agency, whereby they gather and process information and distribute them within the Keiretsu system. Specifically, foreign data are fed into the networks. The information is mainly disseminated through clubs, company-wide committees and councils. (Grabowiecki)

But not only concerning the role as an information agency, coordinator and leading supplier and customer the trading houses are pivotal within the Keiretsu system, also when it comes to corporate finance. While the bank pursues financial resources externally, the task for the trading houses is to expand the group's markets. Trading houses and banks within the Keiretsu system are mutually complementary.

From the main bank point of view, the trading house is not only an optimal borrower (low risk, minimal monitoring cost, etc.), it also is an attractive customer (foreign currency and other monetary transactions, financing exports, etc.). Whereas from the point of view of the trading house, the main bank is the optimum partner as it always can offer the best terms because of its concentrated market strength.

Furthermore, the bank always has an incentive to offer special terms when it comes to dealing with the trading house. The financial relationships of the trading house with the other group members of the Keiretsu are manifold. In general one could say that while the main bank acts as leading financier during periods of expansion of the Keiretsu, the trading company financially accompanies the expansion phase. For example does the trading company loan and guarantee provisions when additional funds are required and invested in new projects and/or in R&D during the expansion phase. More importantly though, the trading house gets active during times of general uncertainty by granting loans to suppliers, providing extended payment terms of credit, etc. This "quasi-banking function" of the trading house is one of the major feature of the Keiretsu system and explains why the term "financial conglomerate" is used to define them. (Grabowiecki)

But the role of the trading firm is constantly changing with the ongoing restructuring of Japan's economy away from heavy, industrial, and capital-intensive products toward lighter, consumer, and knowledge-intensive industries. It is to be observed that the proportion of group trade conducted by the sogo- shosha and group companies involving heavy and industrial is diminishing. Light and consumer product are increasing in importance.

In addition, companies that are involved in newer fields (particularly Toshiba, Toyota, Mitsubishi Electric, and Kirin) have gained on their own the overseas experience and networks that had been the trading company's advantage. Moreover, these products depend less on another of the historical strengths of the trading houses, namely trading in large volumes and capitalizing on small price differentials across markets. (Gerlach)

Instead of moving into newer industries as trading agents, the trading houses are increasingly shifting their attention toward global information acquisition, representing client firms in multiparty negotiations, and arranging and accompanying projects among group companies. The trading houses are now involved in a wide range of functions that facilitate inter-firm trade: searches for and negotiations with trading and joint venture partners, equity participation in resulting projects, ongoing import, export, and other sales business, and post-import financing for final sellers. (Gerlach)

Final Remarks

The sheer size of this Japanese Keiretsu networks creates the overall impression, that corporate Japan is one giant Keiretsu, in which a few indeterminable, apparently boundless edifices have the capacity to directly influence the Japanese economy. The "traditional sector", on the other hand, defined as clearly identifiable and definable legal right, price paradigms, identical organizational structures and power hierarchies, appear to be insignificant. (Grabowiecki)

Nevertheless, companies not forming part of a Keiretsu network do exist in Japan. They are referred to as "soft" industries. They are newer companies and less central to core industrial operations. These include publishing, communications, and air travel, in which the Keiretsu have no involvement, and the broad category of service industries, in which they constitute less than 5 percent of total sales. (Gerlach)

In recent years it is more and more argued that even though the Keiretsu may have at one time been significant, traditional group structures are now breaking down. Even though this perspective is to a certain extend supported by the changes occurring in new technology development, capital financing, and internationalization, the idea that this represents a fundamental transformation is by many seen as greatly exaggerated. They argue that the evidence used in supporting that assumption is largely anecdotal. Where rigorously measurable relationships are considered, these changes appear far weaker.

But it is important to keep in mind that the Keiretsu system in Japan, although not about to disappear, is constantly changing, contracting and evolving. The contraction becomes apparent when considering the declining trend of cross shareholdings in Japan since the onset of the economic crisis the 1990's. In addition, Japanese companies are increasing the number of tie-ups with firms outside their traditional groupings. But this is by no means a sign of traditional group structures breaking down completely in Japan. Neither is it as a new phenomenon. Especially the second phenomenon, i.e. corporate growth through expansion of business partners, is rather a characteristic of Japanese industrial organization, even during the prewar period. Actually, it represents one of the key differences between Japan's historical reliance on the spinning off of operations and the reliance in the United States on intrafirm divisionalization. (Gerlach)

A lot has been changing in Japan's corporate landscape, although often at a glacial pace. How much the future J- System is going to be influenced and changed by organizational and governance components familiar to the west and what is going to stay uniquely Japanese remains to be seen.

Part Three:

Lifetime Employment - The J-System (Part Three)

Source:

Masahiko Aoki; Whither Japan’s Corporate Governance?; Rock Center for Corporate Governance Working Paper No. 29; July 2006

Michael L. Gerlach; Alliance Capitalism: The Social Organization of Japanese Business; University of California Press 1997

Jerezy Grabowiecki; Keiretsu Groups: Their Role in the Japanese Economy and a Reference Point (or a paradigm) for Other Countries; V.R.F Series; No. 413; March 2006

TAKATOSHI ITO; Japan and the Asian Economies: A "Miracle" in Transition; Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; 1996

Dan W. Puchniak; The Efficiency of Friendliness: Japanese Corporate Governance Succeeds again without Hostile Takeovers; Berkeley Business Law Journal; Vol.5; Issue 2; September 2008

Ulrike Schaede; The Strategic Logic of Japanese Keiretsu, Main Banks and Cross-Shareholdings, Working Paper No. 247 Working Paper, revised September 27, 2006

-6-

Pages:

1

2

3

4

5

6

.png)

.png)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment