During the second world war an U.S American statistician called Abraham Wald was asked to advise the U.S Air Force on how to reinforce their planes. An ever increasing number of U.S fighter planes were shot down by the Nazis, but the weight of armour plating applicable during that time was extremely limited.

Thus, the idea of the Air force experts was only a partial reinforcement of their planes. Because the bombers returning from their missions were riddled with bullet holes in the wings, the centre of the fuselage, and the tail, the experts asserted that only those areas should be reinforced.

Rational Decision Making: The Importance of The Invisible

Wald did not agree with the Army experts. He was less interested in what the Air Force saw and knew, but what they could not see and did not know. To Wald the Army experts appeared to be rather ignorant.

The only thing they had discovered was that when planes were hit in the wings, tail or central fuselage, they made it home. The holes in the planes revealed only one thing: The strongest parts of the fighter planes. It showed where a bomber could be shot and still make the flight to the home base. A non problem!

Where, asked Wald, were the planes that had been hit in other areas? Nobody of the experts could give a satisfactory answer, but one thing was certain: They had never returned. Thus, Wald suggested reinforcing the planes wherever the surviving planes had been unscathed.

The abovementioned story should draw the attention of the interested value investor to two extremely important aspects when it comes to stock market investing.

Firstly, beware experts, financial institutions and financial academia. They can be detrimental to your wealth. Wald's case is staggering. The Army experts had the most abundant and best data at hand ,and the stakes could not have been higher. Yet, they failed miserably to see the flaws in their reasoning. Their armoring of the fighter plains would have been in vain had Wald, obviously a man trained to spot human error, not intervened.

But more importantly, be aware of your and your fellow investor's survivorship bias. Because that is the human bias the story unveils. The survivorship bias describes the tendency of human beings to concentrate on people or object that "survived" some process or action and arbitrarily overlooking those that did not.

Human Beings Are Not as Smart as They Think

The survivorship bias tilts our perception of the world in numerous ways, and that almost on a daily basis. Take manufacturing for example. Ever heard someone telling you: "They don't make product xyz anymore like they used to. The craftsmanship skills in former times was way superior to now!"

A totally skewed comment the person making it is not even aware of. For sure all the goods of former times that are surrounding him must have had a high standard of manufacturing in order to survive. But he is totally unaware of the great majority of objects produced during those "marvellous" times that were junk and have been scrapped or otherwise disposed of.

Ever heard of the study that claimed that cats falling from less than six stories have greater injuries than cats who fall from higher than six stories? The scientists reasoned that cats reach terminal velocity after righting themselves at about five stories. After this point they relax, leading to less severe injuries. What about reasoning that this phenomenon is nothing more than a prime example of the survivorship bias? How likely is it that cats dying in such falls are brought to a veterinarian? Thus, how many of the cats killed in falls from higher buildings are not included in the study? I bet a great many!

Another example for the survivor bias is looking for advise of very old people how to become a centenarian. But all you can expect is being advised by someone who has not died already. Take Dorothy Peel who celebrated her 111th birthday in 2013. She claims that her longevity is down to booze, cigs and that she never had children.

Before cancelling your gym membership and heading strait to the next off- license you better think again. Because most of the people who made Dorothy's health choices are already resting in peace and cannot tell you about how bad of an idea it was succumbing to a daily regime of 20 cigars, knuckle of pork, cheese sticks and 6 pints of beer.

Performance Measures And Survivorship Bias: What We Cannot See But Still Matters

The concept of survivor bias is well worth being aware of, especially when you work in the field of finance. Because it explains the tendency for failed companies to be excluded from performance studies.

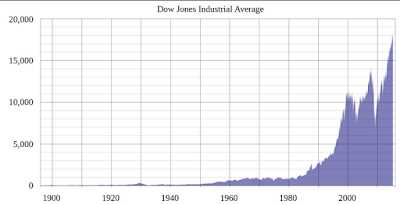

Think of the world's most famous stock index, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA). It was created in 1896 by Charles Dow and originally consisted of 12 companies. In 1929, the Dow Jones was expanded to include 30 companies. To state that the DJIA has seen a lot of turnover in its history is rather an understatement. Only one of the original 12 members, General Electrics, continues to hold a place in it.

Most people think that the DJIA indexes the stock prices of the 30 most prominent U.S. companies. Well it does, but only until the point where the companies cease to be that prominent and other companies raising to prominence. Because every know and than does a company perform so poorly that it is kicked out of this prestigious index and is replaced by a superior company.

What does the DJIA than really reflect? Certainly a different reality than many talking heads and market pundits presume. It is biased toward survivors or, if you want to think about the phenomenon more broadly, toward the winners.

It is not my intention to water down my reader's cheerfulness about Corporate Americas successes in the past or optimism about it in the future. Its performance certainly was, and very likely will be, exceptional. Nevertheless, whenever academia, experts and market pundits proclaiming the superiority of Corporate America by citing the relentless ascent of the Dow Jones over time as evidence, it is worth keeping the survivor bias in mind.

The Mutual Fund Industry And The Survivorship Bias

The survivorhip bias is the one that so frequently results in skewed findings in measuring financial performance. It tricks the casual observer to interpret a performance presentation much more favorable than it really is.

Take the mutual fund industry for example. Not only their clients, but even the promotors of mutual funds themselve are susceptible to falling pray of the survivorship bias. At any given time, the great majority of mutual funds will claim to be in the top rank of performers when compared to their peers. Technically they are correct. But only because so many of their competitors closed down their funds or merged because of underperformance.

Similarly, the survivorship bias in finance also manifest itself in measuring the relative performance of different investment strategies over time. Examining the relative performance of a group of strategies money managers pursue, and still are in business today, will be seriously biased to the upside. Because it is only considering those who survived and neglects the ones that had dropped out because of their poor performance.

Hence, when evaluating the performance of money managers, indices, strategies and the mutual fund industry as a whole, one has to be careful to include both the winners and the losers. All you ever are presented by Wall Street and their cheerleaders are the successes. Money pundits who made great calls in the past are considered the heroes of the game. But only because their competitors who made equally bold moves that did not turn- out stumbled and nose dived. Not only is it game over for them, but they have also fallen into obscurity, because they were quickly buried in the land of the invisible.

The Flaws of Best Selling Business Books

Ever read the book Good to Great by Jim Collins? Written in 2001 it would fast become a bestseller in the business community. Basically, it is showcasing eleven companies that were mediocre at best at their beginnings, but at a certain point of time they took off and transformed themselves into a business and stock market darling. Collin's concluded that it was the “culture of discipline” that made this companies so outrageously successful.

One of the eleven “great” companies was Fannie Mae, cuff. Wondering how the other “outstanding” companies have been doing?

You should but you do not. Because Fannie Mae was not even the only case of utter disaster. Anyone who invested in a basket of those companies outlined in Collin's book would have seriously underperformed the S&P 500.

So what did Collins do? Apparently, he started analyzing hundreds of companies in order to come up with 11 good candidates for his book that were matching his criterions. He did not even bother asking whether any of the discarded companies also displayed a certain “culture of discipline” Could it be that many publicly traded companies have such a discipline regardless of their financial or stock market performance? Would one not have been better of as an investor with investing in a basket of such poorly performing companies?

And this best selling business book is not an outlier. Just recall the numerous books claiming the superiority of Japanese companies over their Anglo- Saxon competitors at the height of the Japanese asset bubble. The problem with these kind of business books is a general one. The vast majority of them is backward-looking. They come out when a company, manager or country has been successful for prolonged periods of time. Than the authors try vigorously to figure out what companies, managers and countries did that made them so extremely successful in the past.

What the authors of those books fail to realize is the following. If the past was all what counts in the field of business than librarians would be the richest people in the country. Do not get me wrong. Understanding the past is valuable, but it does by no means predict anything about the future outcome of any undertaking.

The implicit message of these business books is even evil. Because they claim that what they present to their readers did not only make companies, countries, business people, investors successful in the past, but that certain traits position them for successes in the indefinite future.

Value Investing and The Relevance of The Invisible

If you spend your life as an investor only learning from the winners, buying books about successful people and companies, and dedicating your time over financial statements of companies that shook the business world, your knowledge of the business world will be severely biased and enormously limited.

When looking for advice in investing, you should look for what not to do. And that is what Graham and Dodd and their likes are offering. The margin of safety they advocate is basically an insurance for the investor's ignorance, limited knowledge and survivorship bias.

Value investors who do nothing more than emulate the strategies of the most successful stock market investors, study only the successful business people, are only interested in the wide moat companies and great compounders of the past should go back to the future. They should imagine going back in time when those "outstanding" investors or companies were mediocre at best and just getting by. They should ask themselves if the outcome of the decisions made by their admired business people were in any way predictable.

When they are intellectually honest with themselves, they would admit that they are seeing patterns in hindsight where there was only chaos in the moment.

Reference:

Whitney, WO; Mehlhaff, CJ (1987). "High-rise syndrome in cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 191

Business Advice Plagued by Survivor Bias (Asmartbear)

Survivorship Bias (Youarenotsosmart)

Survivorship Bias (Thefreedictionary.com)

Survivor Bias on the Gridiron (Freakonomics.com/)

Who were the original Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) companies? (Investopedia.com)

WHERE ARE THEY NOW? The 12 members of the 1896 Dow Jones Industrial Average (Businessinsider.com)

Pages:

1

2

One of the things I love about indices and index funds besides their diversification benefits is that they're less prone to survivorship bias. Their historical performance reflects the performance of companies that are no longer traded today. But if we go into Google Finance or Yahoo Finance, they will not give us the historical data of stocks that are no longer traded today and this inflates our backtesting results since we can only backtest using the "surviving" stocks.

ReplyDeleteYou can pick some stocks that have been trading since the 1970s and put them together in a portfolio that beats the market but that doesn't mean such a portfolio would perform well going forward; you probably would not have known in 1970 which stocks trading then would still be traded in 2016.